Battle of the Chesapeake

| Battle of the Chesapeake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American War of Independence and Siege of Yorktown (1781) | |||||||

The French line (left) and British line (right) do battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 24 ships of the line with 1,542 guns[2] | 19 ships of the line with 1,410 guns[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

220 killed or wounded 2 ships damaged[4] |

90 killed 246 wounded 5 ships damaged 1 ship scuttled[4][5] | ||||||

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 1781. The combatants were a British fleet led by Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves and a French fleet led by Rear Admiral François Joseph Paul, the Comte de Grasse. The battle was strategically decisive,[1] in that it prevented the Royal Navy from reinforcing or evacuating the besieged forces of Lieutenant General Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia. The French were able to achieve control of the sea lanes against the British and provided the Franco-American army with siege artillery and French reinforcements. These proved decisive in the Siege of Yorktown, effectively securing independence for the Thirteen Colonies.

Admiral de Grasse had the option to attack British forces in either New York or Virginia; he opted for Virginia, arriving at the Chesapeake at the end of August. Admiral Graves learned that de Grasse had sailed from the West Indies for North America and that French Admiral de Barras had also sailed from Newport, Rhode Island. He concluded that they were going to join forces at the Chesapeake. He sailed south from Sandy Hook, New Jersey, outside New York Harbor, with 19 ships of the line and arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake early on 5 September to see de Grasse's fleet already at anchor in the bay. De Grasse hastily prepared most of his fleet for battle—24 ships of the line—and sailed out to meet him. The two-hour engagement took place after hours of maneuvering. The lines of the two fleets did not completely meet; only the forward and center sections fully engaged. The battle was consequently fairly evenly matched, although the British suffered more casualties and ship damage, and it broke off when the sun set. The British tactics have been a subject of debate ever since.

The two fleets sailed within view of each other for several days, but de Grasse preferred to lure the British away from the bay where de Barras was expected to arrive carrying vital siege equipment. He broke away from the British on 13 September and returned to the Chesapeake, where de Barras had since arrived. Graves returned to New York to organize a larger relief effort; this did not sail until 19 October, two days after Cornwallis surrendered.

[The] Battle of the Chesapeake was a tactical victory for the French by no clearcut margin, but it was a strategic victory for the French and Americans that sealed the principal outcome of the war.

Background

[edit]During the early months of 1781, both pro-British and rebel separatist forces began concentrating in Virginia, a state that had previously not had action other than naval raids. The British forces were led at first by the turncoat Benedict Arnold, and then by William Phillips before General Charles, Earl Cornwallis, arrived in late May with his southern army to take command.

In June, Cornwallis marched to Williamsburg, where he received a confusing series of orders from General Sir Henry Clinton that culminated in a directive to establish a fortified deep-water port (which would allow resupply by sea).[7] In response to these orders, Cornwallis moved to Yorktown in late July, where his army began building fortifications.[8] The presence of these British troops, coupled with General Clinton's desire for a port there, made control of the Chesapeake Bay an essential naval objective for both sides.[9][10]

On 21 May, Generals George Washington and Rochambeau, respectively the commanders of the Continental Army and the Expédition Particulière, met at the Vernon House in Newport, Rhode Island to discuss potential operations against the British and Loyalists. They considered either an assault or siege on the principal British base at New York City, or operations against the British forces in Virginia. Since either of these options would require the assistance of the French fleet, then in the West Indies, a ship was dispatched to meet with French Lieutenant général de Grasse who was expected at Cap-Français (now known as Cap-Haïtien, Haiti), outlining the possibilities and requesting his assistance.[11] Rochambeau, in a private note to de Grasse, indicated that his preference was for an operation against Virginia. The two generals then moved their forces to White Plains, New York, to study New York's defenses and await news from de Grasse.[12]

Arrival of the fleets

[edit]De Grasse arrived at Cap-Français on 15 August. He immediately dispatched his response to Rochambeau's note, which was that he would make for the Chesapeake. Taking on 3,200 troops, De Grasse sailed from Cap-Français with his entire fleet, 28 ships of the line. Sailing outside the normal shipping lanes to avoid notice, he arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 30 August,[12] and disembarked the troops to assist in the land blockade of Cornwallis.[13] Two British frigates that were supposed to be on patrol outside the bay were trapped inside the bay by De Grasse's arrival; this prevented the British in New York from learning the full strength of de Grasse's fleet until it was too late.[14]

British Admiral George Brydges Rodney, who had been tracking De Grasse around the West Indies, was alerted to the latter's departure, but was uncertain of the French admiral's destination. Believing that de Grasse would return a portion of his fleet to Europe, Rodney detached Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood with 14 ships of the line and orders to find de Grasse's destination in North America. Rodney, who was ill, sailed for Europe with the rest of his fleet in order to recover, refit his fleet, and to avoid the Atlantic hurricane season.[3]

Sailing more directly than de Grasse, Hood's fleet arrived off the entrance to the Chesapeake on 25 August. Finding no French ships there, he then sailed for New York.[3] Meanwhile, his colleague and commander of the New York fleet, Rear Admiral Sir Thomas Graves, had spent several weeks trying to intercept a convoy organized by John Laurens to bring much-needed supplies and hard currency from France to Boston.[15] When Hood arrived at New York, he found that Graves was in port (having failed to intercept the convoy), but had only five ships of the line that were ready for battle.[3]

De Grasse had notified his counterpart in Newport, Barras, of his intentions and his planned arrival date. Barras sailed from Newport on 27 August with 8 ships of the line, 4 frigates, and 18 transports carrying French armaments and siege equipment. He deliberately sailed via a circuitous route in order to minimize the possibility of a battle with the British, should they sail from New York in pursuit. Washington and Rochambeau, in the meantime, had crossed the Hudson on 24 August, leaving some troops behind as a ruse to delay any potential move on the part of General Clinton to mobilize assistance for Cornwallis.[3]

News of Barras' departure led the British to realize that the Chesapeake was the probable target of the French fleets. By 31 August, Graves had moved his five ships of the line out of New York Harbor to meet with Hood's force. Taking command of the combined fleet, now 19 ships, Graves sailed south, and arrived at the mouth of the Chesapeake on 5 September.[3] His progress was slow; the poor condition of some of the West Indies ships (contrary to claims by Admiral Hood that his fleet was fit for a month of service) necessitated repairs en route. Graves was also concerned about some ships in his own fleet; Europe in particular had difficulty manoeuvring.[16]

Battle lines form

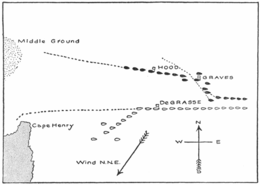

[edit]French and British patrol frigates each spotted the other's fleet around 9:30 am; both at first underestimated the size of the other fleet, leading each commander to believe the other fleet was the smaller fleet of Admiral de Barras. When the true size of the fleets became apparent, Graves assumed that de Grasse and Barras had already joined forces, and prepared for battle; he directed his line toward the bay's mouth, assisted by winds from the north-northeast.[2][17]

De Grasse had detached a few of his ships to blockade the York and James Rivers farther up the bay, and many of the ships at anchor were missing officers, men, and boats when the British fleet was sighted.[2] He faced the difficult proposition of organizing a line of battle while sailing against an incoming tide, with winds and land features that would require him to do so on a tack opposite that of the British fleet.[18] At 11:30 am, 24 ships of the French fleet cut their anchor lines and began sailing out of the bay with the noon tide, leaving behind the shore contingents and ships' boats.[2] Some ships were so seriously undermanned, missing as many as 200 men, that not all of their guns could be manned.[19] De Grasse had ordered the ships to form into a line as they exited the bay, in order of speed and without regard to its normal sailing order.[20] Admiral Louis de Bougainville's Auguste was one of the first ships out. With a squadron of three other ships Bougainville ended up well ahead of the rest of the French line; by 3:45 pm the gap was large enough that the British could have cut his squadron off from the rest of the French fleet.[21]

By 1:00 pm, the two fleets were roughly facing each other, but sailing on opposite tacks.[22] In order to engage, and to avoid some shoals (known as the Middle Ground) near the mouth of the bay, Graves around 2:00 pm ordered his whole fleet to wear, a manoeuvre that reversed his line of battle, but enabled it to line up with the French fleet as its ships exited the bay.[23] This placed the squadron of Hood, his most aggressive commander, at the rear of the line, and that of Admiral Francis Samuel Drake in the vanguard.[22][24]

At this point, both fleets were sailing generally east, away from the bay, with winds from the north-northeast.[2] The two lines were approaching at an angle so that the leading ships of the vans of both lines were within range of each other, while the ships at the rear were too far apart to engage. The French had a firing advantage, since the wind conditions meant they could open their lower gun ports, while the British had to leave theirs closed to avoid water washing onto the lower decks. The French fleet, which was in a better state of repair than the British fleet, outnumbered the British in the number of ships and total guns, and had heavier guns capable of throwing more weight.[22] In the British fleet, Ajax and Terrible, two ships of the West Indies squadron that were among the most heavily engaged, were in quite poor condition.[25] Graves at this point did not press the potential advantage of the separated French van; as the French centre and rear closed the distance with the British line, they also closed the distance with their own van. One British observer wrote, "To the astonishment of the whole fleet, the French center were permitted without molestation to bear down to support their van."[26]

The need for the two lines to actually reach parallel lines so they might fully engage led Graves to give conflicting signals that were interpreted critically differently by Admiral Hood, directing the rear squadron, than Graves intended. None of the options for closing the angle between the lines presented a favourable option to the British commander: any manoeuvre to bring ships closer would limit their firing ability to their bow guns, and potentially expose their decks to raking or enfilading fire from the enemy ships. Graves hoisted two signals: one for "line ahead", under which the ships would slowly close the gap and then straighten the line when parallel to the enemy, and one for "close action", which normally indicated that ships should turn to directly approach the enemy line, turning when the appropriate distance was reached. This combination of signals resulted in the piecemeal arrival of his ships into the range of battle.[27] Admiral Hood interpreted the instruction to maintain line of battle to take precedence over the signal for close action, and as a consequence his squadron did not close rapidly and never became significantly engaged in the action.[28]

Battle

[edit]It was about 4:00 pm, over 6 hours since the two fleets had first sighted each other, when the British—who had the weather gage, and therefore the initiative—opened their attack.[22] The battle began with HMS Intrepid opening fire against the Marseillois, its counterpart near the head of the line. The action very quickly became general, with the van and center of each line fully engaged.[22] The French, in a practice they were known for, tended to aim at British masts and rigging, with the intent of crippling their opponent's mobility. The effects of this tactic were apparent in the engagement: Shrewsbury and HMS Intrepid, at the head of the British line, became virtually impossible to manage, and eventually fell out of the line.[29] The rest of Admiral Drake's squadron also suffered heavy damage, but the casualties were not as severe as those taken on the first two ships. The angle of approach of the British line also played a role in the damage they sustained; ships in their van were exposed to raking fire when only their bow guns could be brought to bear on the French.[30]

The French van also took a beating, although it was less severe. Captain de Boades of the Réfléchi was killed in the opening broadside of Admiral Drake's Princessa, and the four ships of the French van were, according to a French observer, "engaged with seven or eight vessels at close quarters."[30] The Diadème, according to a French officer "was utterly unable to keep up the battle, having only four thirty-six-pounders and nine eighteen-pounders fit for use" and was badly shot up; she was rescued by the timely intervention of the Saint-Esprit.[30]

The Princessa and Bougainville's Auguste at one point were close enough that the French admiral considered a boarding action; Drake managed to pull away, but this gave Bougainville the chance to target the Terrible. Her foremast, already in bad shape before the battle, was struck by several French cannonballs, and her pumps, already overtaxed in an attempt to keep her afloat, were badly damaged by shots "between wind and water".[31]

Around 5:00 pm the wind began to shift, to British disadvantage. De Grasse gave signals for the van to move further ahead so that more of the French fleet might engage, but Bougainville, fully engaged with the British van at musket range, did not want to risk "severe handling had the French presented the stern."[32] When he did finally begin pulling away, British leaders interpreted it as a retreat: "the French van suffered most, because it was obliged to bear away."[33] Rather than follow, the British hung back, continuing to fire at long range; this prompted one French officer to write that the British "only engaged from far off and simply in order to be able to say that they had fought."[33] Sunset brought an end to the firefight, with both fleets continuing on a roughly southeast tack, away from the bay.[34]

The center of both lines was engaged, but the level of damage and casualties suffered was noticeably less. Ships in the rear squadrons were almost entirely uninvolved; Admiral Hood reported that three of his ships fired a few shots.[35] The ongoing conflicting signals left by Graves, and discrepancies between his and Hood's records of what signals had been given and when, led to immediate recriminations, written debate, and an eventual formal inquiry.[36]

Standoff

[edit]That evening, Graves did a damage assessment. He noted that "the French had not the appearance of near so much damage as we had sustained", and that five of his fleet were either leaking or virtually crippled in their mobility.[34] De Grasse wrote that "we perceived by the sailing of the English that they had suffered greatly."[37] Nonetheless, Graves maintained a windward position through the night, so that he would have the choice of battle in the morning.[37] Ongoing repairs made it clear to Graves that he would be unable to attack the next day. On the night of 6 September he held council with Hood and Drake. During this meeting Hood and Graves supposedly exchanged words concerning the conflicting signals, and Hood proposed turning the fleet around to make for the Chesapeake. Graves rejected the plan, and the fleets continued to drift eastward, away from Cornwallis.[38] On 8 and 9 September the French fleet at times gained the advantage of the wind, and briefly threatened the British with renewed action.[39] French scouts spied Barras' fleet on 9 September, and de Grasse turned his fleet back toward the Chesapeake Bay that night. Arriving on 12 September, he found that Barras had arrived two days earlier.[40] Graves ordered the Terrible to be scuttled on 11 September due to her leaky condition, and was notified on 13 September that the French fleet was back in the Chesapeake; he still did not learn that de Grasse's line had not included the fleet of Barras, because the frigate captain making the report had not counted the ships.[41] In a council held that day, the British admirals decided against attacking the French, due to "the truly lamentable state we have brought ourself."[42] Graves then turned his battered fleet toward New York,[43][44] arriving off Sandy Hook on 20 September.[43]

Aftermath

[edit]

The British fleet's arrival in New York set off a flurry of panic amongst the Loyalist population.[45] The news of the defeat was also not received well in London. King George III wrote (well before learning of Cornwallis's surrender) that "after the knowledge of the defeat of our fleet [...] I nearly think the empire ruined."[46]

The French success left them firmly in control of the Chesapeake Bay, completing the encirclement of Cornwallis.[47] In addition to capturing a number of smaller British vessels, de Grasse and Barras assigned their smaller vessels to assist in the transport of Washington's and Rochambeau's forces from Head of Elk to Yorktown.[48]

It was not until 23 September that Graves and Clinton learned that the French fleet in the Chesapeake numbered 36 ships. This news came from a dispatch sneaked out by Cornwallis on 17 September, accompanied by a plea for help: "If you cannot relieve me very soon, you must be prepared to hear the worst."[49] After effecting repairs in New York, Admiral Graves sailed from New York on 19 October with 25 ships of the line and transports carrying 7,000 troops to relieve Cornwallis.[50] It was two days after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown.[51] General Washington acknowledged to de Grasse the importance of his role in the victory: "You will have observed that, whatever efforts are made by the land armies, the navy must have the casting vote in the present contest."[52] The eventual surrender of Cornwallis led to peace two years later and British recognition of a new, independent United States of America.[51]

Admiral de Grasse returned with his fleet to the West Indies. In a major engagement that ended Franco-Spanish plans for the capture of Jamaica in 1782, he was defeated and taken prisoner by Rodney in the Battle of the Saintes.[53] His flagship Ville de Paris was lost at sea in a storm while being conducted back to England as part of a fleet commanded by Admiral Graves. Graves, despite the controversy over his conduct in this battle, continued to serve, rising to full admiral and receiving an Irish peerage.[54]

Analysis

[edit]Many aspects of the battle have been the subject of both contemporary and historical debate, beginning right after the battle. On 6 September, Admiral Graves issued a memorandum justifying his use of the conflicting signals, indicating that "[when] the signal for the line of battle ahead is out at the same time with the signal for battle, it is not to be understood that the latter signal shall be rendered ineffectual by a too strict adherence to the former."[55] Hood, in commentary written on the reverse of his copy, observed that this eliminated any possibility of engaging an enemy who was disordered, since it would require the British line to also be disordered. Instead, he maintained, "the British fleet should be as compact as possible, in order to take the critical moment of an advantage opening ..."[55] Others criticise Hood because he "did not wholeheartedly aid his chief", and that a lesser officer "would have been court-martialled for not doing his utmost to engage the enemy."[56]

One contemporary writer critical of the scuttling of the Terrible wrote that "she made no more water than she did before [the battle]", and, more acidly, "If an able officer had been at the head of the fleet, the Terrible would not have been destroyed."[42] Admiral Rodney was critical of Graves' tactics, writing, "by contracting his own line he might have brought his nineteen against the enemy's fourteen or fifteen, [...] disabled them before they could have received succor, [... and] gained a complete victory."[46] Defending his own behaviour in not sending his full fleet to North America, he also wrote that "[i]f the admiral in America had met Sir Samuel Hood near the Chesapeake", that Cornwallis's surrender might have been prevented.[57]

United States Navy historian Frank Chadwick believed that de Grasse could have thwarted the British fleet simply by staying put; his fleet's size would have been sufficient to impede any attempt by Graves to force a passage through his position. Historian Harold Larrabee points out that this would have exposed Clinton in New York to blockade by the French if Graves had successfully entered the bay; if Graves did not do so, Barras (carrying the siege equipment) would have been outnumbered by Graves if de Grasse did not sail out in support.[58]

According to scientist/historian Eric Jay Dolin, the dreaded hurricane season of 1780 in the Caribbean (a year earlier) may have also played a crucial role in the outcome of the 1781 naval battle. The Great Hurricane of 1780 in October was perhaps the deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record. An estimated 22,000 people died throughout the Lesser Antilles with the loss of countless ships from many nations. The Royal Navy's loss of 15 warships with 9 severely damaged crucially affected the balance of the American Revolutionary War, especially during Battle of Chesapeake Bay. An outnumbered British Navy losing to the French proved decisive in Washington's Siege of Yorktown, forcing Cornwallis to surrender and effectively securing independence for the United States of America.[59]

Memorial

[edit]At the Cape Henry Memorial located at Joint Expeditionary Base Fort Story in Virginia Beach, Virginia, there is a monument commemorating the contribution of de Grasse and his sailors to the cause of American independence. The memorial and monument are part of the Colonial National Historical Park and are maintained by the National Park Service.[60]

Order of battle

[edit]British line

[edit]| British fleet | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Commander | Casualties | Notes | ||

| Killed | Wounded | Total | |||||

| Van (rear during the battle) | |||||||

| Alfred | Third rate | 74 | Captain William Bayne | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Belliqueux | Third rate | 64 | Captain James Brine | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Invincible | Third rate | 74 | Captain Charles Saxton | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Barfleur | Second rate | 98 | Rear Admiral Samuel Hood Captain Alexander Hood |

0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Monarch | Third rate | 74 | Captain Francis Reynolds | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Centaur | Third rate | 74 | Captain John Nicholson Inglefield | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Centre | |||||||

| America | Third rate | 64 | Captain Samuel Thompson | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bedford | Third rate | 74 | Captain Thomas Graves | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Resolution | Third rate | 74 | Captain Lord Robert Manners | 3 | 16 | 19 | |

| London | Second rate | 98 | Rear Admiral Thomas Graves Captain David Graves |

4 | 18 | 22 | Fleet flag |

| Royal Oak | Third rate | 74 | Captain John Plumer Ardesoif | 4 | 5 | 9 | |

| Montagu | Third rate | 74 | Captain George Bowen | 8 | 22 | 30 | |

| Europe | Third rate | 64 | Captain Smith Child | 9 | 18 | 27 | |

| Rear (van during the battle) | |||||||

| Terrible | Third rate | 74 | Captain William Clement Finch | 4 | 21[61] | 25 | Scuttled after the battle |

| Ajax | Third rate | 74 | Captain Nicholas Charrington | 7 | 16 | 23 | |

| Princessa | Third rate | 70 | Rear Admiral Francis Samuel Drake Captain Charles Knatchbull |

6 | 11 | 17 | Rear flag |

| Alcide | Third rate | 74 | Captain Charles Thompson | 2 | 18 | 20 | |

| Intrepid | Third rate | 64 | Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy | 21 | 35 | 56 | |

| Shrewsbury | Third rate | 74 | Captain Mark Robinson | 14 | 52 | 66 | |

| Casualty summary | 82 | 232 | 314 | ||||

| Unless otherwise cited, table information is from The Magazine of American History With Notes and Queries, Volume 7, p. 370. The names of the ship captains are from Allen, p. 321. | |||||||

French line

[edit]Sources consulted (including de Grasse's memoir, and works either dedicated to the battle or containing otherwise detailed orders of battle, like Larrabee (1964) and Morrissey (1997)) do not list per-ship casualties for the French fleet. Larrabee reports the French to have suffered 209 casualties;[37] Bougainville recorded 10 killed and 58 wounded aboard Auguste alone.[31]

The exact order in which the French lined up as they exited the bay is also uncertain. Larrabee notes that many observers wrote up different sequences when the line was finally formed, and that Bougainville recorded several different configurations.[23]

The 74-gun Glorieux and Vaillant, as well the other frigates, remained at the mouth of the various rivers that they were guarding.[62]

See also

[edit]- American Revolutionary War § British defeat in America. Places ' Battle of the Chesapeake ' in overall sequence and strategic context.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Duffy 1992, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d e Morrissey, p. 54

- ^ a b c d e f Mahan, p. 389

- ^ a b Castex, p. 33

- ^ Morrissey, p. 56

- ^ Weigley, p. 240

- ^ Ketchum, pp. 126–157.

- ^ Grainger, pp. 44, 56.

- ^ Ketchum, p. 197

- ^ Linder, p. 15.

- ^ Mahan, p. 387

- ^ a b Mahan, p. 388

- ^ Ketchum, pp. 178–206

- ^ Mahan, p. 391

- ^ Grainger, p. 51

- ^ Larrabee, p. 185

- ^ Larrabee, pp. 186, 189

- ^ Larrabee, p. 189

- ^ Larrabee, p. 188

- ^ Larrabee, p. 191

- ^ Larrabee, p. 192

- ^ a b c d e Morrissey, p. 55

- ^ a b Larrabee, p. 193

- ^ Grainger, p. 70

- ^ Larrabee, p. 195

- ^ Larrabee, p. 196

- ^ Larrabee, p. 197

- ^ Grainger, p. 73

- ^ Larrabee, p. 200

- ^ a b c Larrabee, p. 201

- ^ a b c Larrabee, p. 202

- ^ Larrabee, p. 204

- ^ a b Larrabee, p. 205

- ^ a b Larrabee, p. 211

- ^ Larrabee, p. 206

- ^ Larrabee, pp. 207–208

- ^ a b c Larrabee, p. 212

- ^ Larrabee, pp. 213–214

- ^ de Grasse, p. 157

- ^ de Grasse, p. 158

- ^ Larrabee, pp. 220–222

- ^ a b Larrabee, p. 220

- ^ a b Morrissey, p. 57

- ^ Allen, p. 323

- ^ Larrabee, p. 225

- ^ a b Larrabee, p. 272

- ^ Ketchum, p. 208

- ^ Morrissey, p. 53

- ^ Larrabee, p. 227

- ^ Grainger, p. 135

- ^ a b Grainger, p. 185

- ^ Larrabee, p. 270

- ^ Larrabee, p. 277

- ^ Larrabee, p. 274

- ^ a b Larrabee, p. 275

- ^ Larrabee, p. 276

- ^ Larrabee, p. 273

- ^ Larrabee, p. 190

- ^ "Did Hurricanes Save America?" American Heritage, (Eric Jay Dolin. September 2020. Volume 65. Issue 5). https://www.americanheritage.com/did-hurricanes-save-america

- ^ National Park Service – Cape Henry Memorial

- ^ Misprinted in source as 11.

- ^ a b c Troude (1867), p. 107.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1905), p. 119.

- ^ Gardiner (1905), p. 129.

- ^ Contenson (1934), p. 155.

- ^ a b c d Antier (1991), p. 185.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1905), p. 112.

- ^ Contenson (1934), p. 228.

- ^ a b c Troude (1867), p. 109.

- ^ d'Hozier, p. 305

- ^ a b Gardiner (1905), p. 136.

- ^ Gardiner (1905), p. 127.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1905), p. 128.

- ^ Musée de la Marine (2019), p. 87.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1905), p. 116.

- ^ Revue maritime et coloniale, Volume 75, p. 163

- ^ Gardiner (1905), p. 133.

- ^ Gardiner (1905), p. 130.

- ^ Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 625.

- ^ Annales maritimes et coloniales / 1, Volume 3, p. 32

- ^ Coppolani et al, p. 190

- ^ Contenson (1934), p. 167.

Bibliography

[edit]- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 5852951.

- Antier, Jean-Jacques (1991). L'Amiral de Grasse, héros de l'indépendance américaine. Rennes: Éditions de la Cité, Ouest-France. ISBN 9-782737-308642.

- Contenson, Ludovic (1934). La Société des Cincinnati de France et la guerre d'Amérique (1778–1783). Paris: éditions Auguste Picard. OCLC 7842336.

- Castex, Jean-Claude (2004). Dictionnaire des Batailles Navales Franco-Anglaises. Presses Université Laval. ISBN 2-7637-8061-X.

- Coppolani, Jean-Yves; Gégot, Jean-Claude; Gavignaud, Geneviève; Gueyraud, Paul (1980). Grands Notables du Premier Empire, Volume 6 (in French). Paris: CNRS. ISBN 978-2-222-02720-1. OCLC 186549044.

- Davis, Burke (2007). The Campaign that Won America. New York: HarperCollins. OCLC 248958859.

- Duffy, Michael (1992). Parameters of British Naval Power, 1650–1850. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-385-5. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Gardiner, Asa Bird (1905). The Order of the Cincinnati in France. United States: Rhode Island State Society of Cincinnati. OCLC 5104049.

- Grainger, John (2005). The Battle of Yorktown, 1781: A Reassessment. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-137-2.

- de Grasse, François Joseph Paul; et al. (1864). The Operations of the French fleet under the Count de Grasse in 1781–2. New York: The Bradford Club. OCLC 3927704.

- d'Hozier, Louis (1876). L'Impot du Sang: ou, La Noblesse de France sur les Champs de Bataille, Volume 2, Part 2 (in French). Paris: Cabinet Historique. OCLC 3382096.

- Ketchum, Richard M (2004). Victory at Yorktown: the Campaign That Won the Revolution. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-7396-6. OCLC 54461977.

- Lacour-Gayet, Georges (1905). La marine militaire de la France sous le règne de Louis XVI. Paris: Honoré Champion. OCLC 763372623.

- Larrabee, Harold A (1964). Decision at the Chesapeake. New York: Clarkson N. Potter. OCLC 426234.

- Linder, Bruce (2005). Tidewater's Navy: an Illustrated History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-465-6. OCLC 60931416.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (1890). Influence of sea power upon history, 1660–1783. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1404739154. OCLC 8673260.

- Ministère de la Marine et des Colonies. Revue Maritime et Coloniale, Volume 75 (in French). Paris: Berger-Levrault. OCLC 21397730.

- Musée de la Marine (2019). Mémorial de Grasse (in French). Grasse: Sud Graphique.

- Morrissey, Brendan (1997). Yorktown 1781: The World Turned Upside Down. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-688-0.

- Weigley, Russell (1991). The Age of Battles: The Quest For Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-7126-5856-4.

- Annales maritimes et coloniales / 1, Volume 3 (in French). Paris: L'Imprimerie Royale. 1818. OCLC 225629817.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France (in French). Vol. 2. Challamel ainé.

- Bulletin de la Société d'Etudes Scientifiques et Archéologiques de Draguignan et du Var, Volumes 25–26 (in French). Draguignan: Latil Frères. 1907. OCLC 2469811.

- "National Park Service – Cape Henry Memorial". National Park Service. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries, Volume 7. New York: A. S. Barnes. 1881. OCLC 1590082.

Further reading

[edit]- Clark, William Bell, ed. (1964). Naval Documents Of The American Revolution, Volume 1 (Dec. 1774 – Sept. 1775). Washington D.C., U.S. Navy Department.